"Threadless Corner"

by Ray Klingensmith

Reprinted from "INSULATORS - Crown Jewels of the Wire", February 1980, page 13

"Putting All Your Eggs In One Basket"

It's been

nearly two years in the making, but in some way, the Egg article has finally

hatched. After Shirley Patocka's informative article in the June, 1978, issue of

Crown Jewels, covering the CD 700 and 700.1, I felt I would wait a little while

for collectors to digest the info, and perhaps have time to dig up some material

on the CD 701, the cousin to the CD 700 series.

There are several different

styles of the "egg" insulator with a regular pinhole (one which does

not travel completely through, as with the CD 700). To start things off with

this article, I feel it would be best to begin with what was probably the birth

of the "egg", with a history of William Swain and The Magnetic

Telegraph Company. The Magnetic, the pioneer of private lines in the U.S., was

formed in May, 1845. The building of the line, which was to link New York with

Philadelphia, began in the fall of 1845. Construction began in Philadelphia, and

followed the wagon roads. Norristown, at a distance of fourteen miles, was

reached by early November. Doylestown and Somerville were soon passed, and by

January, 1846, Newark, New Jersey, was reached. Reaching New York City remained

a problem for quite some time, as the early telegraphers had not yet devised a

method of crossing the wide Hudson River with the line. Various methods were

tried, most with little success, for a period of time.

It is interesting to note

the contracts for the line construction specified "insulators of the glass

bureau-knob pattern".

Although the line met with great difficulties, owing

to its early "trial and error" methods (and, may I add, mostly error),

it still managed to become a financial success. Later, it was joined with

Washington, D.C. and various other important cities in the east.

Magnetic Telegraph Company correspondence paper from 1853, showing

office locations and instructions for those sending messages.

Newspaper men

were among those who used the telegraph, and contributed much to its success.

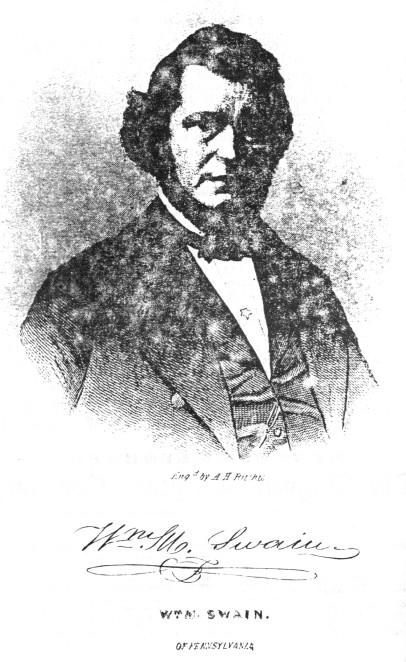

One of these men was William M. Swain, proprietor of The Philadelphia Public

Ledger. Swain was one of those who pledged money to The Magnetic in its early

history. His overwhelming interest for the success of The Magnetic line

eventually resulted in his becoming President of The Magnetic in 1850.

Large Image (255 Kb)

Swain was

a true businessman to the extreme. He was described by various people who were

associated with him as a man of positive character, determination and

hardness. James Reid, in The Telegraph in America, stated that Swain's favorite

motto was "Business is business". After taking over the presidency,

Swain made many changes in company policy which resulted in a large increase in

business. The following is taken from The Telegraph in America, by Reid:

|

As a telegraph officer, he at once gave vigor, method and responsibility to the

business. His predecessor was far too delightful a man for such a position. The

change of administration was felt at once when Swain took the reins. He first

had the outward structure carefully inspected. Although a large man he

personally accompanied the inspect ors of the line on foot over every inch of

the route from New York to Washington! He reported having found 3,000 escapes

and removed them all! He accepted nothing at second-hand. He had the whole line

stiffened, straightened and cleared of obstructions. Not a leaf was allowed to

touch the wires. Not a pole was allowed to lean. He then studied insulation, and

made a sketch of what is known as the egg insulator. "That," he said,

taking me into his office one day, " is the insulator of the future." He deemed

good glass good enough, and the egg shape the form of maximum strength.

That was

the feature which he wanted. The line was quickly stripped of its former

insulation and equipped with egg insulators, first on wooden brackets and

afterward on iron pins. The long gaps of hours during which the service of the

line had often been suspended by rains and crosses and escapes and broken wires,

soon disappeared. |

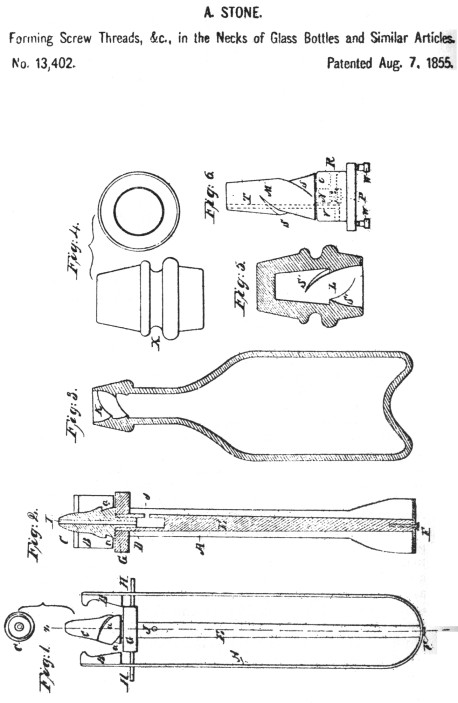

The insulator shown in Reid's book may have been drawn

by Reid himself, and it is difficult to determine by looking at the drawing

whether Swain invented an insulator with a then pinhole or a regular pinhole.

That question has bothered me for quite some time. Some collectors have felt

Swain's invention was in fact the "thru pinhole egg", but I now

believe that style was simply a later variation. In The Telegraph In America,

Reid states ".... equipped with egg insulators, first on wooden brackets

and afterward on iron pins.", in referring to the first use of Swain's egg

insulator on The Magnetic line, which is an indication the pinhole did not carry

completely thru the insulator. The regular deep green eggs (style A) have been

found in the east, where The Magnetic Tel. Co. was located. As near as I can

determine, nearly all of the thru pinhole types have been found in the west,

from lines which would have been constructed at a later date, perhaps the late

1850's and 1860's. Evidence of Swain's "egg" having been of a regular

type is further shown in the following article written by F. L. Pope, appearing

in the September 10, 1871, issue of The Telegrapher.

|

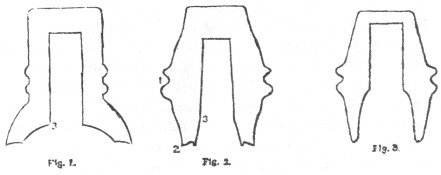

About the year 1850 or '51

Wm. M. Swain, who was then President of the "Old Magnetic Line"

between New York and Washington, designed the well known "egg

insulator," shown in Fig. 2. Considering the imperfect state of electrical

knowledge at that time, there is a wonderful amount of ingenuity and adaptation

to circumstances displayed in this design. It not only stamps its author as a

man of decided originality but also of sound practical common sense. It is very

much to be regretted, on this account, that he did not remain in the telegraph

business the rest of his life.

In designing the model of this insulator Mr.

Swain succeeded in combining excellent insulating qualities with the highest

degree of strength and durability. The general form of the egg or double cone is

the strongest that could possibly have been selected. In fact, it has not been

an uncommon occurrence for one of these insulators to be dropped from the top of

a high pole upon a stone pavement without material injury. Under the ordinary

conditions of exposure in the telegraphic service they are very rarely broken.

In considering its insulating qualities, we find that the conducting surface

constantly grows narrower from the wire at 1 to the support at 3 (see Fig. 2).

During rain a portion of the falling water drips from the flange below the wire

at the point 1, thus reducing the conduction from thence to the point 2. The

insulating space between 2 and 3, although too short (and this is the principal

defect in the design), is of great value in point of resistance, on account of

its narrowness -- or, in other words, its small diameter -- which is rendered

possible by the use of an iron support in place of the wooden pin previously

used. This support was an iron L shaped arm, driven into the post. The whole

formed a most substantial and durable mode of construction, which was actually

better, both in design and execution, than that usually employed at the present

day.

The effect of the adoption of Mr. Swain's improvements in

telegraphic construction upon the receipts of the Magnetic Company's lines was

as follows:

CASH RECEIPTS OF MAGNETIC TELEGRAPH CO.

| For year ending July 1, 1848 |

$52,252. 81 |

| For year ending July 1, 1849 |

$ 63,367. 62 |

| For year ending July 1, 1850 |

$ 61,383. 98 |

| For year ending July 1, 1851 |

$ 67,787. 12 |

| For year ending July 1, 1852 |

$ 103,860. 81 |

Mr. Swain was elected President in 1850. It

probably required about a year for him to get his improvements well under way,

and the next year following (1852) shows an increase in the receipts of nearly

fifty per cent!

The egg insulator, upon an iron support, was also quite

extensively used from 1851 to 1860 upon many of the telegraph lines in the

Eastern and Middle States.

Figure 3 is an insulator which was taken from an old

Fire Alarm wire in Providence, R.I., and, as near as can he ascertained,

originated in Boston. As will be seen upon inspection, it is an improvement upon

Mr. Swain's model in one very important respect, viz., the narrowness and depth

of the inner cavity. Its only drawback is an insufficiency of material, and

therefore of strength at the top, above the upper end of the support. Like the

Swain model it is designed to be fixed upon an iron arm.

After the egg

insulators had been in use several years the wires began to work very badly, and

show a great deal of escape in wet weather. This was principally caused by the

surface of the glass deteriorating from exposure, and becoming coated with dirt

and smoke from locomotives and other sources.

The true cause, however, was not

at that time understood or even suspected. The managers of telegraph lines

"jumped" to a conclusion, which, as usual, was an erroneous one --

that

the trouble was owing to the egg insulator being too small at the bottom. A

certain distinguished advocate of glass insulation remarked: "When I find

that a parasol is a better thing than an umbrella in a big rain, then I shall

begin to believe that the egg glass insulates better than the umbrella." The iron

supports also came in for a large share of the general condemnation.

So all the

"egg glasses" and iron arms were thrown away, and a new era of

experimenting commenced. Many lines adopted the hard rubber insulator, and

others the Lefferts plug. The advocates of glass returned to the old

"umbrella" (Fig. 1), which they mounted on wooden pins, under the

mistaken idea that these helped the insulation. This was true to a certain

extent, but, on the other hand, the larger opening beneath the insulator,

rendered necessary by the greater diameter of the wooden support, much more than

made up the difference.

Another popular fallacy, that prevailed extensively

about this time, was that the larger the insulator, and the more glass there was

in it, the better it would insulate! This absurd idea, which, it is almost

needless to say, was directly the reverse of the truth, was carried out on a

large scale on many lines that might be mentioned. The result, of course, was

far from satisfactory.

|

Pope's article gives much information as to the

use and development of the egg. The insulator shown in his Fig. 2 is identical

in shape to the insulators (style A) found in the east in a very deep green

color. They are the same in every detail, including the base which has a slight

indentation and a raised ring. The improved insulator (Fig. 3) shows an egg with

a larger skirt interior (style B). Pope states he believes it to have originated

in Boston. It is interesting to note that eggs of that type have been found

throughout the New England area. Before going into detail on the color and style

variations of the eggs, I thought I would cover the development of the

insulator. The following pages, taken from an 1859 book, certainly give a great

deal of info on the various applications of this insulator. It is very

interesting to note the "threaded" egg in the material. Remember, this

was in 1859, and prior to Cauvet's 1865 patent.

|

This insulator was again

improved by Mr. William M. Swain, president of the Magnetic Telegraph Company.

He abolished the flange and constructed the glass in the shape of an egg, as

represented by the following figures.

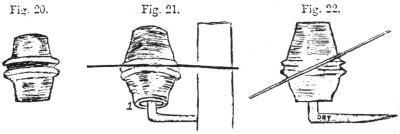

Fig. 20 represents the form of the glass

with line wire groove at its centre. The lower end is concave and the upper

slightly convex. The flange insulator was easily broken, but the egg form cannot

be broken by the ordinary service of the telegraph. I have seen this insulator

thrown as much as a hundred yards, and against brick houses, and not break. This

rotund-shaped glass insures long service, as has been demonstrated by its use on

a long range of lines for many years.

In the arrangement of this insulator Mr.

Swain did not only have in view substantiality, but also the perfection of the

insulation of the line wire from earth currents. At number 1, fig. 21, the cone

is concave. when the water collects upon the upper part of the insulator it does

not follow the glass to the numeral 1, but falls from the centre projection. The

moisture under the drip forms globules, and breaks from the cone at or above 1,

as seen falling from the flange of the cone, fig. 25. The point of drip,

therefore, is not at the lower end, but above at the centre projection as just

described. Fig. 26 represents the drip of a house.

The falling drop breaks the

rain and keeps dry the projection seen under the eave of the house. In

the same manner the dripping from the above described glass insulates the lower

cone from the rain.

Of course the lower end of the glass will not be dry, but

there will be less liability for a watery connections with the earth from the

wire than when the drip is at the lower end of the glass. I have seen this

philosophy illustrated at the Niagara Falls. The immense volume of water passes

over the shelf or point of drip, and beneath the mass of water is a passage-way

for travelers, precisely as represented by fig. 26. If the reader desires to see

this idea illustrated, he can do so by setting a teacup upon an upright pin,

then fill the cup with water until it overflows. The water will fall over the

rim, and the smaller end of the cup will be dry.

Fig. 21 represents the glass

adjusted to the wire when on a right line; fig. 22 when the wire is oblique, as

upon the side of a hill, and fig. 23 when the wire is perpendicular with the

post. In order to prevent the glass from pulling off from the iron arm, the

screw combination represented by fig. 24 was adopted. The iron arm 3, is cut so

that the teeth will serve as a male screw. The glass is made with a female screw

as seen by numeral 2. Fig. 25 represents the glass on the arm, with the line

wire fastened to it at an angle pulling the glass upward, the teeth of the iron

arm fitted into the grooves of the screw prevents the glass from being separated

from the iron arm.

The above figures are engraved with so much variety

that further explanation is unnecessary. They have been gotten up with care, and

they are replete with demonstrative philosophy. |

Large Image (141 Kb)

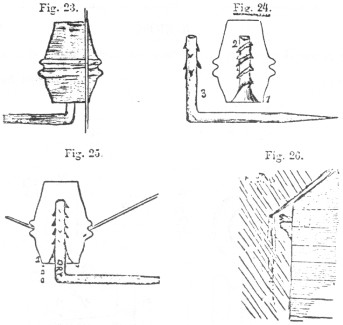

On the previous

page is a copy of a patent issued to Amasa Stone of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

on Aug. 7, 1855. The patent material mentions it was a method of forming screw

threads not only in bottles but also insulators. In fact, insulators are

mentioned throughout the patent application. Amasa Stone is listed as a fruit

jar manufacturer from 1857 to 1861, and in the years 1862 and 1863 as a patent

glassware manufacturer. Fruit jars with the internal threads and matching screw

threaded cap are known to jar collectors. Various sizes of A. Stone jars with

the threading have been found. There also is a rare jar embossed with the name

"The Great Eastern", with a similar threading. The Great Eastern was

the ship which laid the Atlantic Cable in the mid 1860's. This

"jarring" information may seem unimportant, but it indicates Stone was

involved with the actual manufacture of jars made under his patent.

At this time

no egg insulators have been found with the screw thread, but it seems very

likely they were produced. First, they are listed in the 1859 book as being

adopted to prevent the glass from pulling off the iron arm, which indicates the

author of the book probably saw the actual insulator, or was very up to date on

patent information. Second, Amasa Stone was involved with the production of jars

with the screw thread, so it seems likely he also could have produced the

insulator. Third, it is interesting that Stone chose the egg style for the

patent drawing. Remember, Swain, inventor of the egg, and President of The

Magnetic until 1858, was proprietor of a Philadelphia newspaper, Philadelphia

also being Stone's hometown. It seems very likely Stone and Swain could have

known each other and produced the threaded egg.

The Magnetic Telegraph Company

existed until 1859, when it was consolidated into The American Telegraph

Company. The threaded egg could have been used on a Magnetic line prior to the

consolidation, or perhaps later on on an American Telegraph Company line.

In a

phone conversation with Wendall Hunter, who initially brought my attention to

the Stone patent, Wendall mentioned there was also a wealthy Amasa Stone of

Cleveland, Ohio. Wendall stated he believed reading the A. Stone of Cleveland

was on the Board of Directors of the Western Union Telegraph Company, possibly

in the 1860's. This could be the same Amasa Stone that was earlier in

Philadelphia. At the present, I have no proof they are the same person, but most

likely they were. If they were, it shows Stone's interest in the telegraph,

first in a patent showing an insulator, later producing a jar named after the

ship that laid the Atlantic Cable, and still later, on the board of a telegraph

company. So, there are probably threaded eggs out there somewhere!

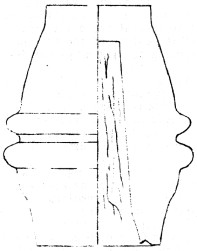

Now, finally

getting to the insulator variations. Most likely the first egg insulators used

on the Magnetic line were of the type shown in Fig. 4 (style A). These have been

found in the east and south. They most likely were used on The Atlantic &

Ohio Telegraph Company line, as one of these was found in a small Pennsylvania

town where that line went through. They were used in New York State on a line

which reportedly gave a lease to the Magnetic, and they have been found in the

southern states.

Amos Kendall, the first president of the Magnetic, labored to

connect the Magnetic line in Washington, D.C. with New Orleans. The Washington

& New Orleans Telegraph Company was formed in 1846 and may be the source of

many of the eggs which have been found in the south. The line connected

Petersburg, Lynchburg, Suffolk and Norfolk, Va., Raleigh, N.C., Augusta,

Savannah, Midville, Atlanta, Macon and Columbus Ga., Montgomery and Mobile,

Ala., and New Orleans. Style A may have also been produced during the

Civil War for the Confederate Army lines. The pinhole interior of the ones used

on the New York State line are marked with many irregular recessed lines as

shown in Fig. 4. This appears to have been done when they were manufactured, to

allow the pin and insulator to be cemented together, having a better hold, due

to the cement filling the small recessed lines. I'm not aware of this method

having been used elsewhere. Style A has been found in deep olive green and a

deep green with a teal tint. The manufacturer of these is unknown at present.

I've always thought perhaps the dark coloring of these and other threadless were

made that way intentionally. Perhaps the reason was the fact that a dark colored

object will absorb heat more readily than a light colored one, and thus

evaporate condensed water from the surface of the insulator at a faster rate,

giving better insulation.

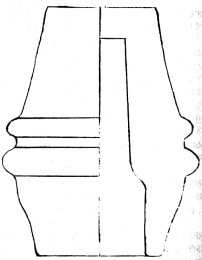

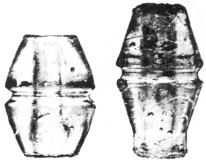

Fig. 4. Style A. Note pinhole begins near base, and base with indentation and

ring, which is prominent on some, nearly

non existent on others.

Size is 3-7/8 x 2-1/16. |

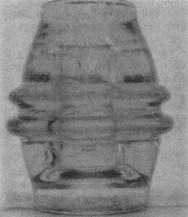

Fig.

5. Style B.

Note pinhole is higher in the insu lator body, and rounded base. This is the "improved egg.

Size

is 4 x 2-1/8. |

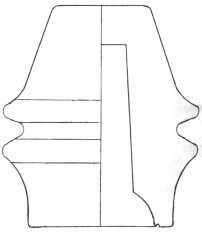

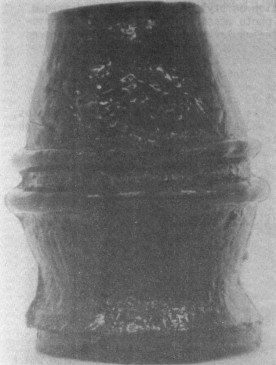

Fig. 6. Style C.

Note indented sides of dome.

Smaller than styles A and B.

Very light green, almost clear. |

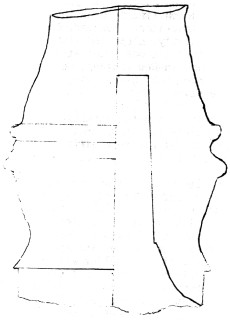

Fig. 7. Style D.

The

"National Road Egg". The smallest of

the glass eggs, measuring 3-1/2 x 2-5/16. |

Dick Bowman photo

Fig. 8 From left to right: a very bubbly aqua style B, 7up

green style B,

lite yellow-green style B, deep teal green style D,

the

"Confederate egg" style F.

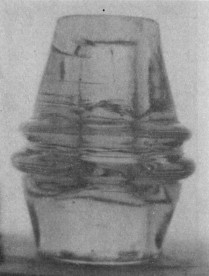

Fig. 9. Style F.

The "Confederate

egg". Note extended base and recessed dome top. Size is a huge 4-3/4 x

2-7/8. |

Fig. 10.

The grey porcelain egg, reported to have been made in Richmond,

Va., ca. 1861. |

Figure 5 shows style B, which F. L. Pope mentioned in the

material written for The Telegrapher, which was shown earlier in this article.

Pope stated "....and as near as can be ascertained, originated in

Boston", referring to style B. I'm not certain if he means that style

originated in Boston, or if the glass was manufactured in Boston. Most likely

style B was produced in the Boston area, as a number have been located

throughout Massachusetts and various New England states. In fact, I'm not aware

of any being found outside the New England area. They have been found in aqua,

bubbly aqua, seven-up green (possibly two different shades), lite yellow-green,

lime green, clear with a grey-sca tint, clear with milky streaks, and there is

rumor of one in cobalt blue! The glass in the clear and lighter colored ones

appears to be of high quality, similar to that used in stemware and other

household glassware.

Doug MacGillvary reported a near clear egg was dug

at the site of the Coventry Glass Company in Connecticut. However, further

research by Doug revealed Coventry went out of business in the 1840's, prior to

the production of the eggs. Perhaps it was used on a nearby telegraph line, or

maybe there was a later glass company at the site which we don't know about.

There also was a clear or near clear egg dug at the Sandwich Glass Company

dumpsite. (Correct name may be Boston & Sandwich Glass Co. I didn't do my

homework.) I was told it had an indentation on the dome which may have been an

imperfection, or perhaps it was like figure 6, style C, which may have been a

different type of mold than style B. At any rate, Sandwich produced clear and

colored glass. They were in business in the 1850's and into the 1870's, if my

memory is correct from the visit I made to the Sandwich Museum four years ago.

Once again, however, there was a telegraph line through the area which may have

been the source of the insulator. However, due to the fact that Sandwich

produced a high quality, clear and light colored glass, among other colors, I

feel that the one found at the site, and perhaps a large part of those found in

New England, were produced at Sandwich. There were a large number of glasshouses

throughout New England, and it's possible several companies produced insulators.

Figure 6, style C, is the same as style B with the exception of the indented

dome. This may have been a manufacturing deformity, but I personally feel it was

intentionally made that way in a different mold than style B, so am classifying

it as a different style. Color is a very lite green, almost clear.

Figure 7,

style D, is a somewhat smaller version than the rest. It has a pinhole somewhat

similar to the revised model (style B), but has the indentation and extending

ring on the base, similar to the base on style A. As near as I can tell, all of

these originated in Ohio, and all may be from a telegraph line which followed

the National Road. There have been threadless insulators found beside and in the

area of the National Road over the years, and it's my belief all the style D

eggs were used on that line. The National Road was an early wagon road which traveled

east and west through Maryland, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana and

Illinois. It eventually linked St. Louis with Washington, D.C. and Baltimore.

Thousands of people used the road in the middle 1800's, and it was the primary

wagon road of the large area in its day. Of the three style D eggs I've seen,

two were aqua, and one was a more sparkling darker shade of blue-aqua. The

darker blue-aqua one was uncovered by a bulldozer doing some excavation for a

modern road which replaced the old National Road.

Style E is a larger egg which

has been found in the south. It is similar to the deep green Magnetic type, but

is taller and wider. (See fig. 8, second from right.) In viewing the regular

sized egg and this larger one "in person", a big difference in their

size can be seen. I believe one of these was found in Virginia and one in

Tennessee. This style has also been found in Mobile Bay, Louisiana. This item is

found in the deep green with a teal tint, and I believe it also is known in the

regular deep green. This item is uniform and neatly made.

Style F

(figures 8, 9 and 13) is a real crude monster measuring 4-3/4" tall by

2-7/8" wide at the base. This insulator in my opinion is the most crudely

made of all insulators. It looks like a piece of dark green wax which a three

year old child has just carved with a knife in the shape of an insulator! This

insulator is very near in shape to style E, except that this one has a long

extended base and is crudely made. The surface on this large insulator is very

coarse and pebbly. The wire groove at some pints is nearly filled with glass,

and the dome top is recessed into the insulator. (The dome top is formed in a

saucer of bowl-like depression -- see Fig. 9.) The base on these flares out

forming a concave skirt and has an extension which projects downward 1/2 inch.

The extension is on all of the style F units I've seen, and I would guess they

were intentionally made that way. These are nicknamed "The Confederate

Egg" because of their being found in areas once occupied by Confederate

troops during the Civil War. This insulator was found in Mobile Bay where the

Confederate Army reportedly built a telegraph line on a bridge across the bay.

(Also found with these were styles A and E.) One also was found along a railroad

right of way near Richmond, Va.

I sometimes wonder if perhaps the mold used to

produce style E was badly damaged in some way, perhaps by overheating, or

exposure to water, which resulted in a rough surface on the mold interior.

Assuming these were made during the Civil War, for Confederate use, the main

factor concerned would be good insulation, and not a nicely made insulator. So,

in my opinion, the style E mold could have been damaged and altered, and the

style F egg then produced in the same mold. It's also quite possible that with a

lack of proper equipment to make a fine mold, during the Civil War, a Southern

manufacturer made one as best it could, using a style E egg for a model. One must

remember that supplies in the south at that time were very limited, due to the

fact that the major industrial areas capable of producing equipment were in the

north. Before going on to the next item, I thought I'd point out the fact that

the style F egg has a large pinhole which tapers from 1-1/4 inch at the bottom

to one inch at the top.

Next on the list of eggs is the porcelain, which

measures 3" x 2-5/8". These have been assigned U970 in Jack Tod's

Universal Style Chart for porcelain. I know of five of these in collections. One

of these was found at the site of an encampment of the Alabama Department of the

Confederacy near Dunfries, Va. Between twenty and thirty were found at the

bottom of the old Kanawha Canal several years ago by someone who didn't know

they had any value, and unfortunately left them there. Sorry to say, they are

now buried under tons of dirt. These are reported to have been made in Richmond,

Va. at Parr's Pottery in 1861. There are two reports on their use -- one on a

telegraph line parallel to the railroad between Richmond and Fredericksburg, and

the other on a line between Richmond and Yorktown. Of the five I know of, three

have a lite cream-tan glaze, and one a grey glaze. Dick Bowman reported his has

a nail through the body of the insulator! Dick stated the nail is rusted, and it

appears as though a hole was made in the skirt area prior to the firing of the

porcelain, and perhaps when placed on a pin, the nail was inserted. If you can't

cement a threadless to a pin, why not nail it on! One of the other porcelain

eggs I saw had a repaired area on the dome and appeared as though an attempt was

made to drive a nail hole, and in the field a line constructor got the idea of

driving the nails into them; but, as stated, Dick indicated the hole in his

appeared to have been made prior to firing it. All this is very interesting, and

I wonder how the nail driven into the pin may have affected insulation!

At present there are seven distinctively different styles of eggs. It appears

these were in use from 1850 or 1851 and probably until or shortly after 1870. I

had believed they were probably no longer produced after the Civil War, but the

ad shown above indicates otherwise. I believe this was from the March 1868 issue

of The Telegrapher. Bartlett was offering "Eggs" at that time, and one

could assume they are referring to that type covered in this article. I'm not

sure if Bartlett was in Boston or New York. I would assume it to be New York, as

that is where The Telegrapher was printed, and the ad doesn't indicate another

city. Bartlett probably was from there also.

Fig. 11

The "thru pinhole

type" eggs. From The Glass Insulator-- A Comprehensive Reference by

Cranfill & Kareofelas. |

Fig. 12.

Various iron brackets used on an "egg

line" in New York, shown with style A insulator used on that line, and

style F used in the South. |

Fig. 13 Style F.

The big crude monster. |

Paul

Plunkett photo

Fig. 14. The seven up green style B. |

Paul Plunkett photo

Fig. 15.

A bubbly aqua style B. |

Fig. 16.

The lime green style B. High quality glass

similar to that for household use. |

The brackets shown in figure 12 are

all from the New York State line described in the information on style A. They

are hand forged iron. The longest one in the photo measures 14-1/2 inches.

Unfortunately for collectors, when the insulators and brackets were removed from

the poles, it appears as though a hammer or large object was used to smash them off

the pole, breaking all the insulators.

If anyone has any additional information

or color/style variations not listed, please contact me (Ray Klingensmith, 709

Rt. 322, East Orwell, OH 44034), so that is can be placed in an upcoming

"Threadless Corner". A big thanks to the following people for photos,

information, written material, and also for allowing me to photograph items in

their collections, etc.: Dick Bowman, The Branhams, Gary Cranfill, Dennis

Donovan, Glenn Drummond, Fred Griffin, Wenall Hunter, Mike Johnson, Frank Jones,

Greg Kareofelas, Doug MacGillvary, Mike Sovereign, and the Paul Plunkett

family.

|